Since John Locke's work on empiricism in 1689, we have embraced what is now known as the scientific method. This method is based on four laws: observability, measurability, replicability, and drawing the smallest possible inference from the data. These principles guided science for nearly 250 years.

In 1935, Karl Popper advanced the scientific method with the falsification method, also known as post-empirical science. This approach, with its emphasis on rigorous testing and falsifiability, significantly influenced the study of psychology, leading to the development of measurement tools known as psychometrics. These tools, or psychological tests, are evaluated for their scientific rigor using various techniques such as validity and reliability. These evaluations ensure the trustworthiness of the test results. The two main measures of importance in this context are discriminant validity and internal reliability.

Noam Chomsky highlighted that science is both a rationalist and empiricist pursuit. Theories are rational links that combine empirical findings together and predict where to search for new empirical facts. This is true of The GreyScale as it combines the various scales from the assessment together.

The GreyScale, is an assessment designed for modern leadership, addresses many of the validity and reliability issues that other older assessments have yet to address and is anchored in a rationalist theory of how the leader’s personality through their containment factors affects the psychosocial forces that impact on the team’s ability to function. The following sections identify and explain these issues.

Validity

Overview

When considering the use of any test, ensuring its validity should be a top priority. A valid test measures what it claims to measure. For example, using a measuring tape to measure someone’s height is valid because it accurately measures height. However, asking someone their age to determine their height would not be valid, as age and height differ.

Validity is assessed in various ways. Unfortunately, validity is sometimes used to create the impression that a test is scientifically sound when it may not be. It is also essential to understand that test validity is not about the honesty of the test taker.

The Greyscale uses the term "authenticity" to refer to test-taker behaviours. This concept involves the application of 11 different measures and strategies to assess whether the test-taker is responding honestly or merely trying to present themselves in a certain way.

Face Validity

In psychometric testing, one problematic type of validity is ‘face’ validity. This refers to whether someone without specialised knowledge can easily identify what a test is assessing. If they can, the test is said to have high face validity.

However, this can be an issue. If a test is designed to measure something seen as positive, test takers might figure out how to answer in a way that produces the desired result rather than reflecting their true thoughts or behaviours.

Therefore, an effective test should include questions that someone without specialised knowledge cannot easily interpret. This prevents individuals from "gaming" the test and responding based on how they want to be perceived rather than their actual characteristics.

Discriminate Validity

If a test claims to measure more than one thing, the scores for those different aspects should vary independently. If both scores are always either high or low, it suggests that the test is measuring just one thing. Discriminant validity checks if the different aspects being measured are independent.

For example, height and age are somewhat correlated during the first 20 years of life, but they become independent in the following 80 years. There are short elderly and short young people, indicating that height and age are distinct variables. Therefore, a low score for discriminant validity indicates that the things being measured are different.

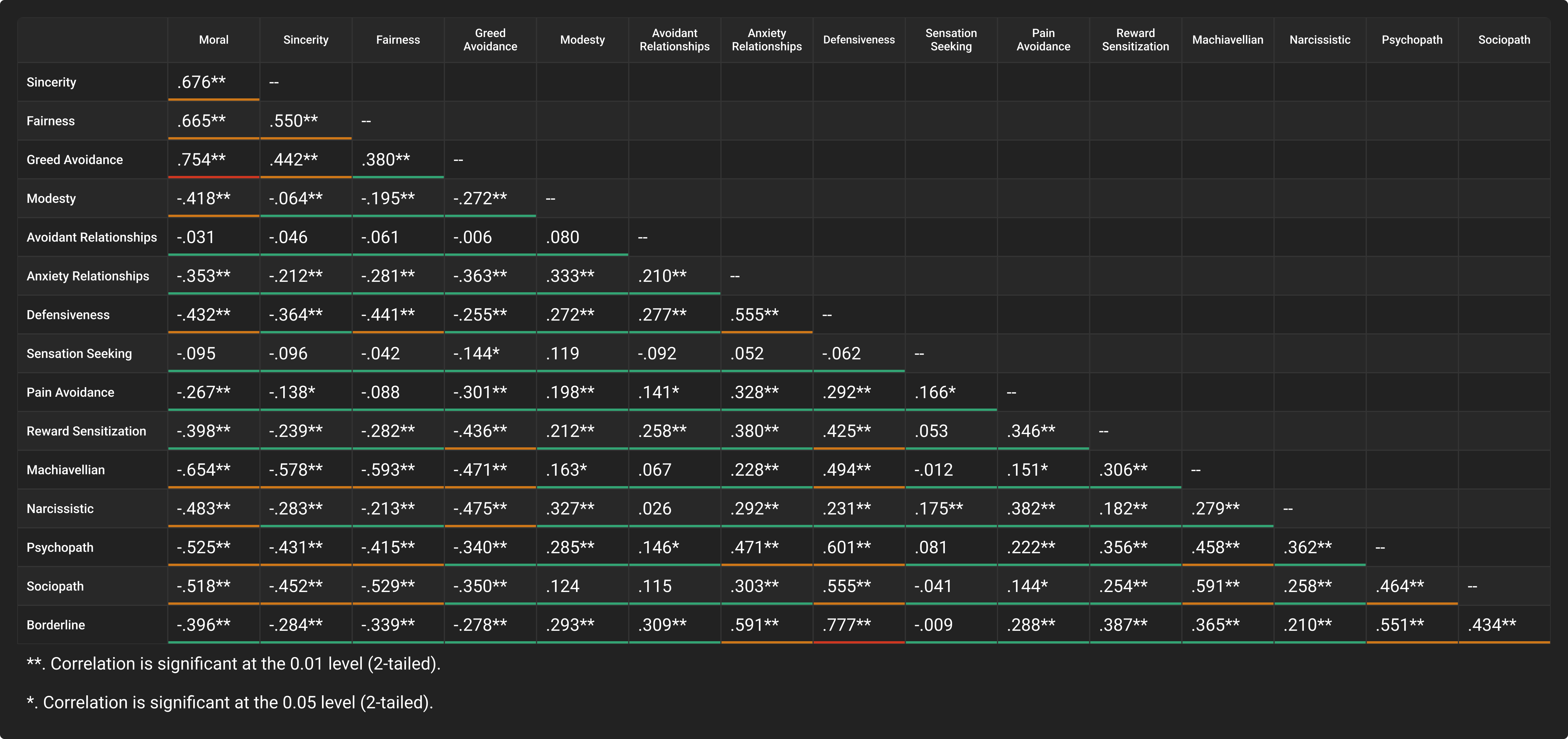

TGS has only two correlations that are high, greed avoidance with Morals and Borderline with defensiveness. All others are moderate or low with the vast majority 74% being in the ideal low range. This demonstrates each factor being measured is independent.

Convergent Validity

People often mistakenly believe that convergent validity is vitally important. Convergent validity refers to how well a test or scale produces similar results to other tests or scales that claim to measure the same thing. This concept, however, poses several challenges.

Firstly, if a test or scale is the first of its kind, there are no existing tests or scales against which to compare it. This makes it impossible to establish convergent validity. Additionally, if the definition of what is being tested differs slightly between tests, the results will also vary, making it hard to determine if the level of convergence is appropriate.

The second issue with convergent validity is that it can fall into the logical fallacy of appeal to consensus. Just because multiple tests agree (showing high convergent validity) doesn't necessarily mean they are correct. For example, if ten people claim the earth is flat, their agreement doesn’t make it true even though they have perfect convergent validity.

Reliability

Overview

Reliability refers to the consistency of a test across different contexts. Test-retest reliability measures whether the test produces consistent results over time when the assessed trait is expected to remain stable. Internal reliability assesses whether the different questions on a test measure the same underlying concept. Inter-rater reliability evaluates whether the test yields the same results when administered by different people. Each type of reliability ensures that the test is dependable and produces consistent results in its respective context.

Internal Reliability

Internal reliability is the most critical reliability score when evaluating which test to use and trust. Internal reliability reflects how well the test maker has grouped questions to create a coherent scale. This is critical because all subsequent interpretations, recommendations, and actions are based on these scales. If the internal reliability is poor, any conclusions drawn from the test will likely be flawed.

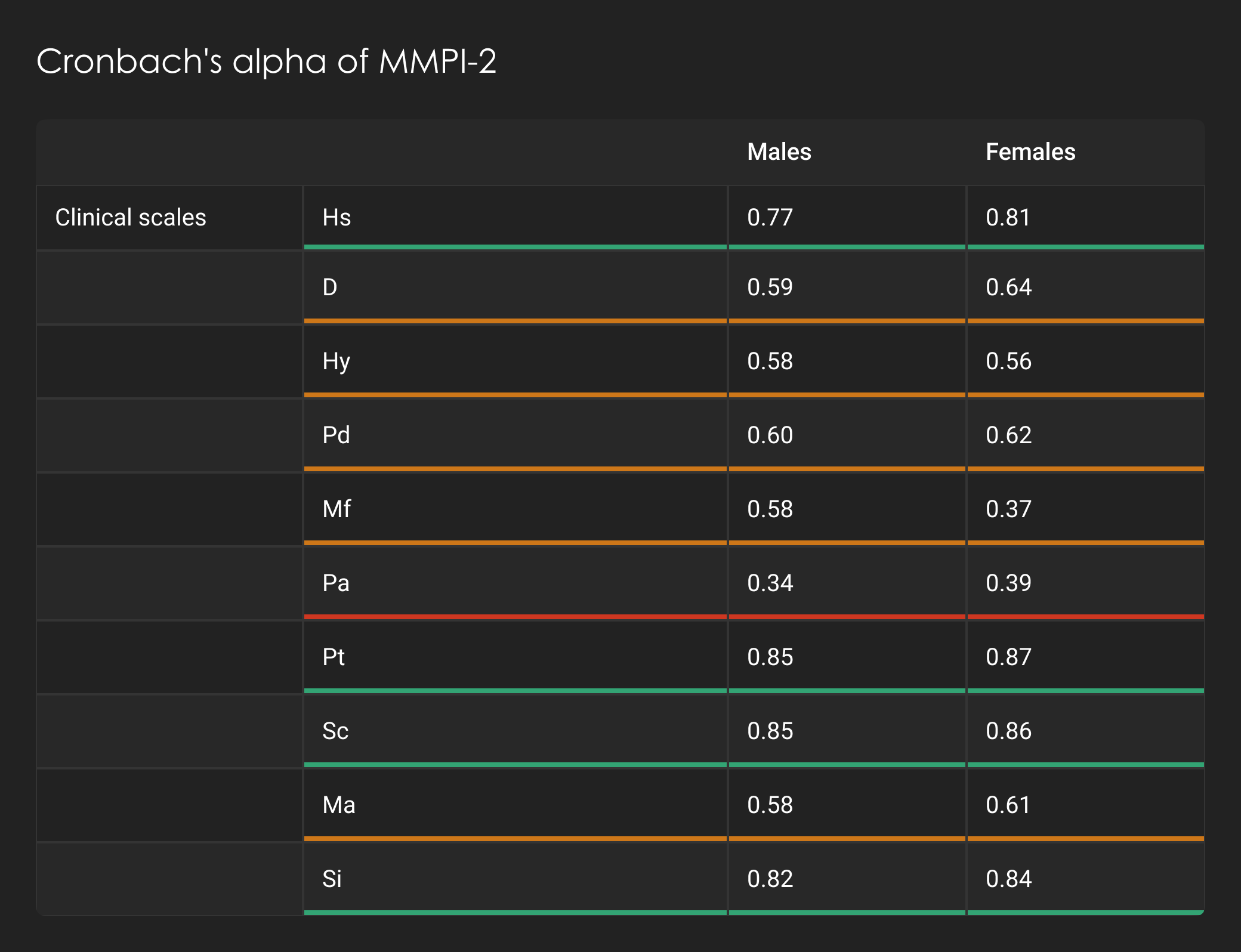

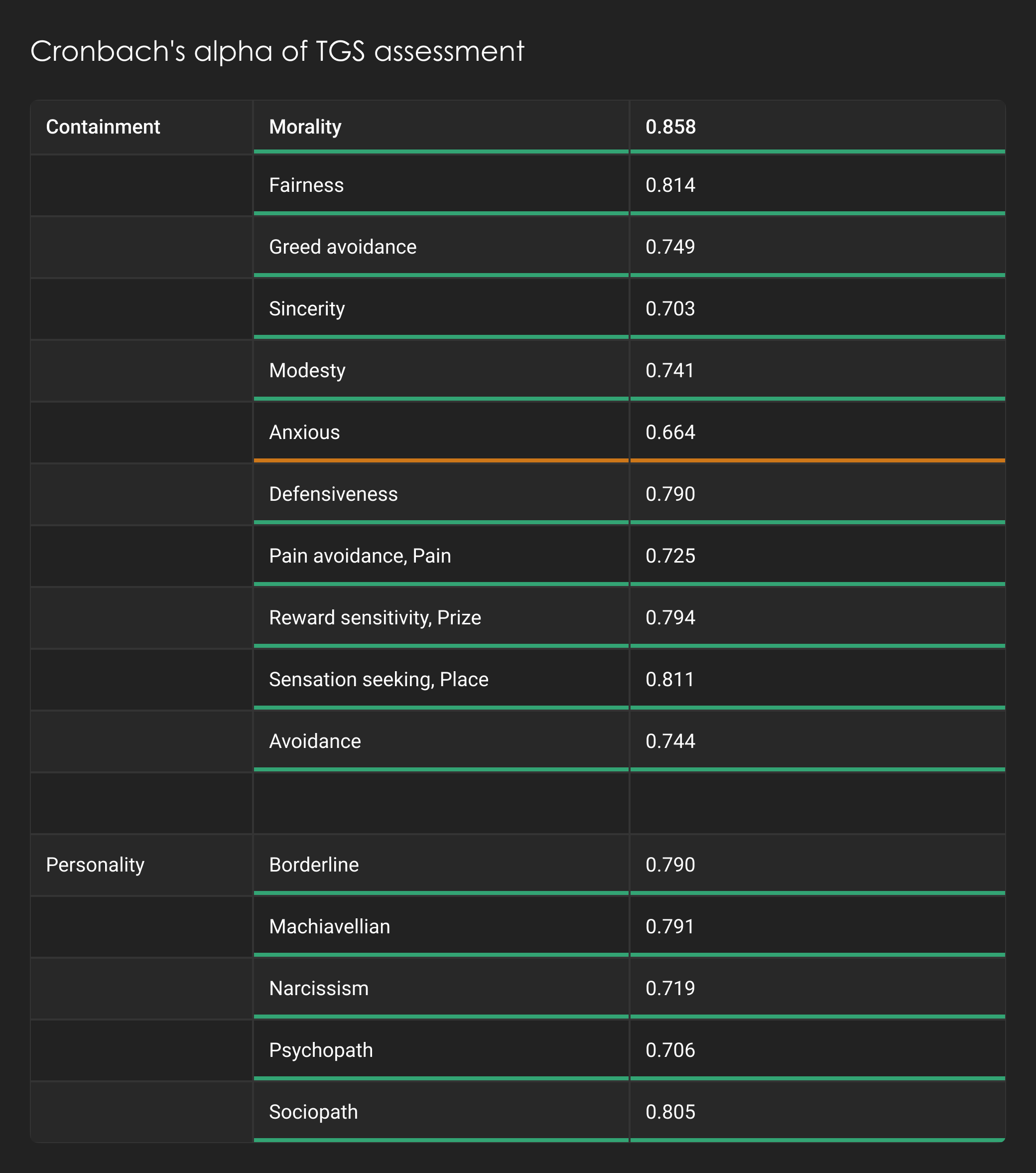

Internal reliability is assessed using a mathematical function called Cronbach's alpha. The higher, but not too high, the Cronbach's alpha score, the better the internal reliability of the test, ensuring more accurate and reliable results. As can be seen the MMPI-2, which is the most widely researched and well used test in psychology for diagnosing mental illness, has published Cronbach alpha's for its scales. These are shown below. Most of the scales are either green or yellow. The GreyScale's Cronbach alphas are also shown below with only one scale being yellow.

Test-retest Reliability

Some tests assess attributes claimed to be stable, meaning these attributes are expected to stay mostly the same over time. For example, fear induced by watching a horror movie is temporary and should change once the movie ends, resulting in low test-retest reliability. In contrast, when measured with a reliable test like the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, a person's IQ should remain stable over time, reflecting high test-retest reliability, typically ranging from 0.7 to 0.9.

While relatively stable, personality factors are not as consistent as IQ. For instance, the MMPI-2 (Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory) shows test-retest reliability ranging from 0.48 to 0.8, indicating that personality traits have moderate stability over time.

Inter-rater Reliability

Tests and tools are designed for multiple people and should yield consistent results across users. Inter-rater reliability assesses whether different people using the tool or test obtain similar outcomes. For example, if one person uses a screwdriver to turn a screw, inter-rater reliability checks if another person can achieve the same result using the same screwdriver.

Inter-rater reliability becomes especially important for qualitative tests that require interaction with an assessor. When a test is self-administered, without an assessor or qualitative changes, inter-rater reliability is not a concern, as the rater does not vary. TGS does not use a rater

Test Development

Overview

Building a test is a complex process that involves multiple iterations and developmental stages. It combines rational thinking with empirical data testing, ensuring that the final product leverages the strengths of both approaches.

Most tests' initial set of questions, including the TGS test, is created rationally. This means the questions are designed based on what people believe will effectively investigate the topic. While this rational approach ensures that the questions should, in theory, assess the intended subject, it often results in questions too related to what they aim to measure, leading to high face validity.

After the initial list of questions is created, it undergoes empirical assessment. A group completes the questions, and their responses are analysed mathematically to determine if they effectively function as a scale. During this stage, the internal reliability of the scale is evaluated. It is common for many questions that seemed appropriate during the rational phase to be discarded at this point. For instance, when developing The GreyScale test, nearly one-third of the questions were eliminated.

The significance of removing these questions cannot be overstated. Experts in the field initially selected what they believed were the best questions on the topic, the ones they would ask in an interview. However, one-third of these questions were ineffective, acting as distractions and complicating the understanding of the subject. This demonstrates why quantitative scales built with empirical validation are far superior to qualitative, rational interviewing. Imagine making decisions based on those one-third of ineffective questions! And remember, you don’t know which one-third is the useless one-third!

How Leaders Impact People

Overview

Using The GreyScale assessment involves recognising a leader's significant impact on team functioning and performance. A leader is not merely a figurehead collecting a paycheck; they are crucial in how well the team operates and accomplishes tasks. This understanding is grounded in the thematic analysis of various psychosocial stressors affecting people at work.

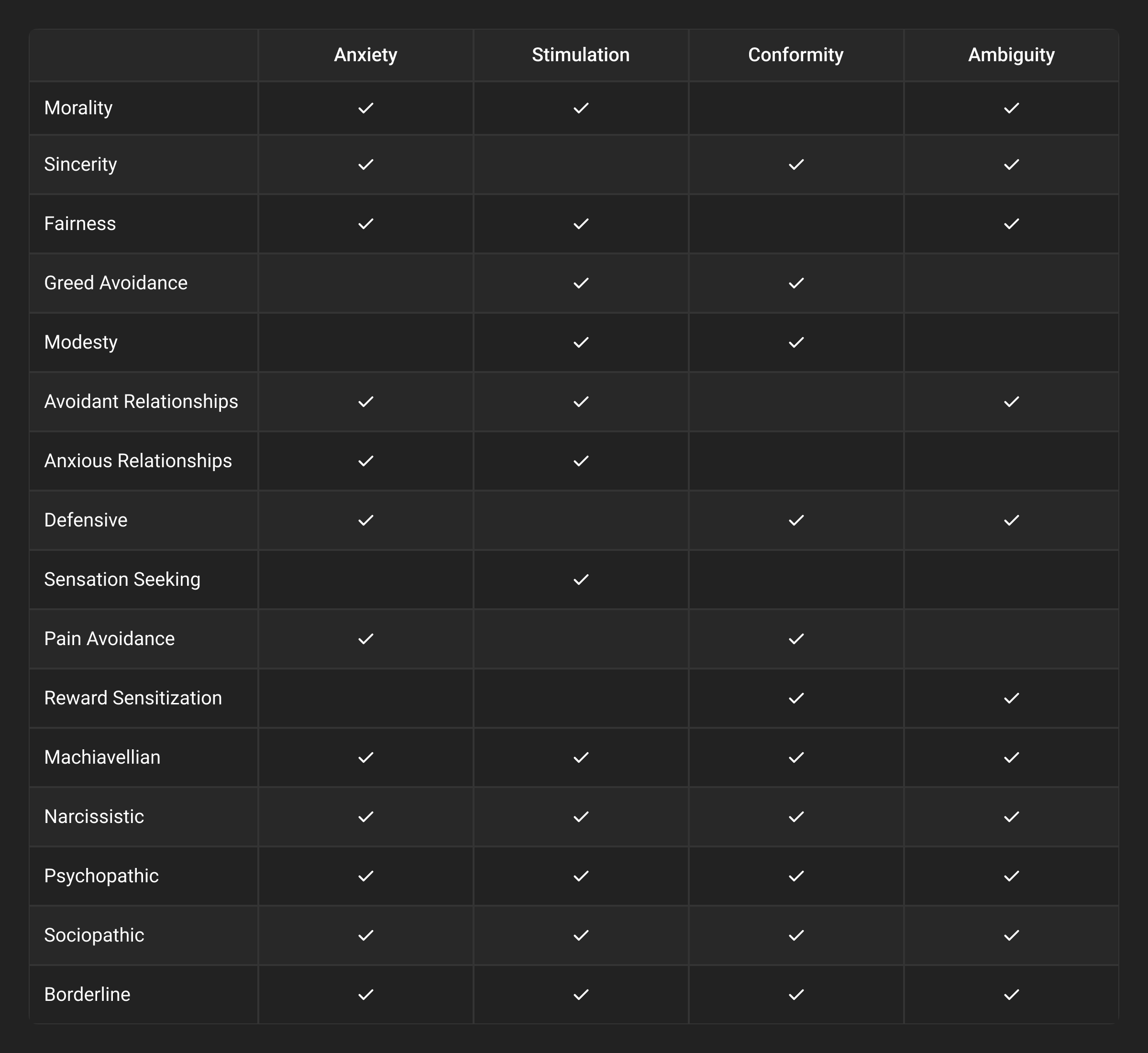

The literature identifies four main themes: Anxiety, Stimulation, Conformity, and Ambiguity (ASCA). These elements naturally occur in the work environment. Unfortunately, we rarely operate with complete and accurate information (the opposites of anxiety and ambiguity), perfect freedom (the opposite of conformity), and ideal conditions (the opposite of overstimulation). Instead, we often work with incomplete information, constraints, and suboptimal environments.

An essential task for a leader is to mitigate the negative impact of this mismatch between the desired and actual work conditions for their team. An effective leader minimizes the negative effects of ASCA, while a toxic leader amplifies them. An ineffective leader tends to have little impact.

This premise was further validated through literature assessing how each component of leadership impacts ASCA. This led us to develop a matrix illustrating how each measured scale of a leader interacts with the ASCA factors

How Leaders Impact Function and Performance

Overview

Function and performance are distinct concepts. Function pertains to how well a person is functioning overall, often measured by their levels of distress or stress. Regardless of skill level, a person experiencing high levels of distress or stress is less likely to function or perform effectively. Chronic or extreme distress and stress can lead to mental illnesses, which is the focus of emerging global psychosocial safety laws.

Performance refers to a person’s ability to do a job by applying their skills and talents, which is underpinned by Bandura’s concept of self-efficacy—the belief in one's capability to execute tasks. Self-efficacy can be general, where a person feels generally competent and skilled, or specific, relating to tasks like riding a bike, racing a car, or performing work-related duties. General and specific self-efficacy influence each other, and extensive research demonstrates their impact on nearly all performance domains in life, more so than self-esteem.

Traditionally, higher skill levels have been assumed to lead to lower distress. However, our research revealed the opposite: ASCA (Anxiety, Stimulation, Conformity, and Ambiguity) directly affects distress and stress, not self-efficacy (whether general or specific). This explains why highly skilled professionals like doctors can still experience significant distress. Their skills do not shield them from the impacts of ASCA; instead, ASCA directly influences their levels of distress and stress.

This insight challenges the traditional approach of addressing distress by improving individual skills and self-efficacy. Instead, the focus should be on managing the forces that contribute to ASCA, which directly affect distress and stress levels. The leader is the critical factor in influencing ASCA. Effective leadership can reduce ASCA’s negative impact, while poor or toxic leadership can amplify ASCA.

Forensic-style Psychometric Tools

Overview

There is an established manner in which a forensic-styled test assesses a person’s answers. It is a logical progression that must occur in a series of steps. The first step must be completed and passed to move on to the next step. A step cannot be bypassed or ignored. This is the same process as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory 2 (MMPI-2), the most well-researched psychological test in the world used in courts worldwide.

Step 1: Completion

Did the person answer enough questions to provide enough data to analyze? This is generally set at at least 95% per scale within the test.

Step 2: Understanding

Did the person answer questions in a manner that confirms that they understood the questions? This assesses random responding and inconsistent responding.

Step 3: Exaggerating Negatives

Did the person answer questions that indicate some extremely negative responses? This can be that the responses are extremely rare or negative about the person responding.

Step 4: Exaggerating Positive

Did the person answer questions that endorse positive qualities and deny everyday faults?

Step 5: Scales of Interest

These are the various scales that the test is designed to assess in the person once the previous four steps have been passed. So, for the MMPI-2, it is for various mental illnesses; for the TGS, it is the personality traits and containment factors.

The TGS test employs this same process. Steps 1 through 4 are referred to as the “authenticity” scales so as not to confuse the test taker's validity with the scientific assessment of the test’s validity. There are 11 different scales across the 4 steps that assess these aspects in various ways.

TGS Solutions to Meet Your Unique Needs

TGS provides leadership performance evaluation solutions for businesses, recruitment firms, and individual leaders. Our solutions are built around The TGS Leadership Assessment.

It delivers powerful, actionable insights to increase leadership effectiveness; identify and mitigate leadership toxicity and risk; and improve leadership candidate suitability, along with an in-depth analysis of distributed leadership.